JHU has stopped collecting data as of

After three years of around-the-clock tracking of COVID-19 data from...

Building trust in vaccination

Vaccines are one of the most effective medical interventions available and save millions of lives each year.1 Despite this, vaccine-preventable diseases are re-emerging and vaccine acceptance remains suboptimal for routine immunizations as well as other immunizations.2 Unfortunately, the vaccines themselves don’t save lives. Vaccination is what saves lives.

What is vaccine hesitancy?

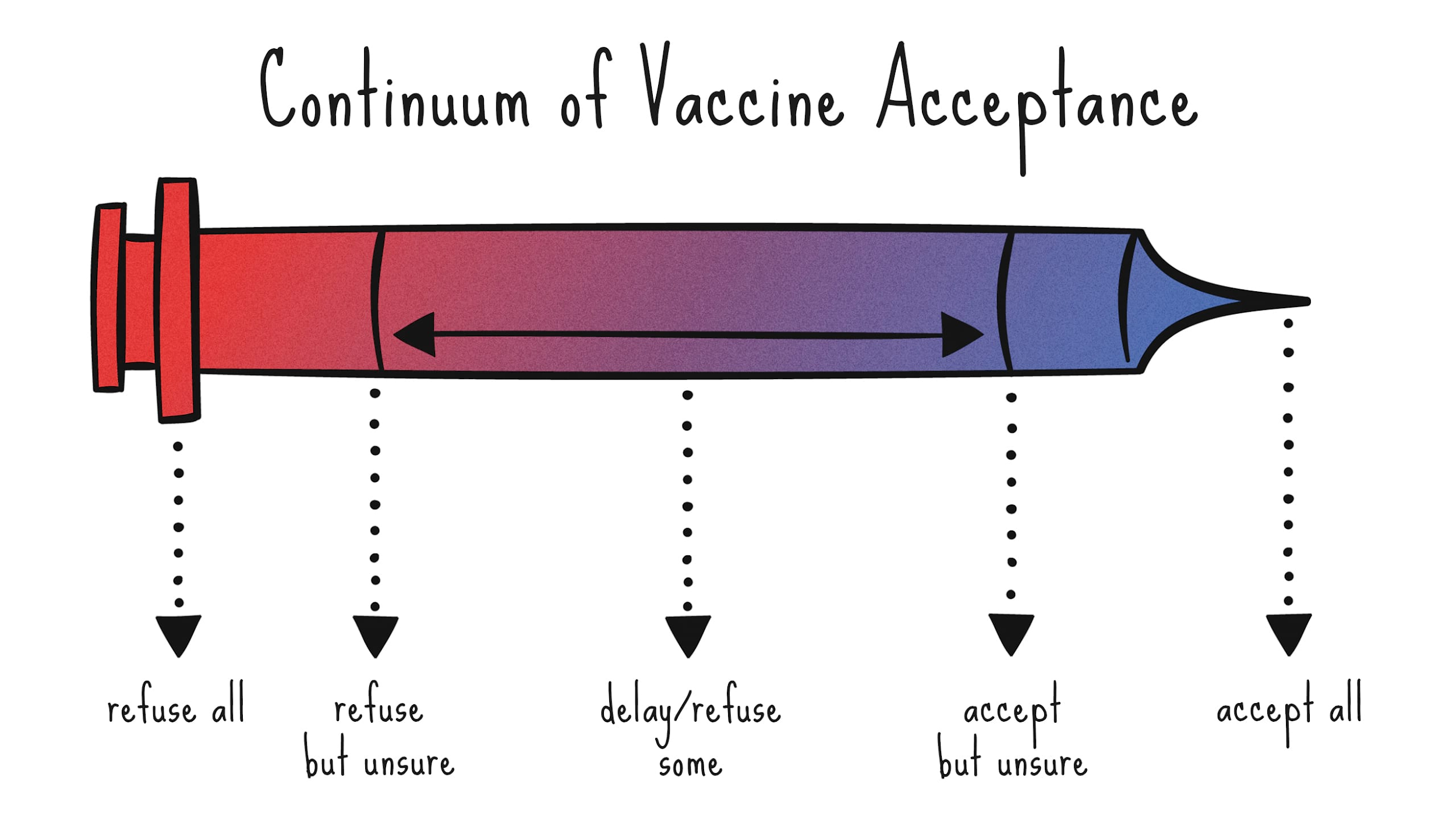

Attitudes toward vaccines fall on a continuum (Figure 1). While we have many effective and safe vaccines available, an increasing number of individuals can be classified as vaccine hesitant.3 Individuals in this group may refuse some vaccines, agree to others, delay vaccines, or accept vaccines but are uncertain about this decision.4 Vaccine refusal has been associated with increased risk of contracting vaccine-preventable disease,2 and vaccine hesitancy is troubling because of its effects on herd immunity at the population level.5

What is driving vaccine hesitancy?

Vaccine uncertainty has led to more individuals questioning vaccines,6 and delaying or refusing vaccines7; as the pandemic has increased uncertainty in many facets of our lives,8 it has also led to high levels of Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy.9 Determinants of vaccine hesitancy can be grouped into domains: contextual influences, individual and group influences including societal and peer norms, and vaccine-specific influences that are related to vaccine characteristics or the vaccination process.10

Within the context of Covid-19, several drivers of vaccine hesitancy have been identified. Safety is the most pressing driver, including quality control and side effects, in part due to concerns related to the rapid development of vaccines.11 Vaccine effectiveness is another factor.12 Another issue is the sheer amount of misinformation, largely being disseminated via social media platforms.13

In the U.S., the reasons for hesitancy vary across sub-groups; Black Americans are more likely to be hesitant than White Americans, rooted in historical trauma and fueled by mistrust of the healthcare system.14 However, a substantial divide also exists along political lines, with Republicans more likely to be hesitant than Democrats.15

Globally, vaccine hesitancy around Covid-19 vaccines varies widely between and within countries. A survey of 32 countries conducted in late 2020 found that 98% of respondents in Vietnam would definitely or probably be vaccinated once a Covid-19 vaccine was available, compared to just 38% of respondents in Serbia.16 The reasons for hesitancy, however, remain the same: concerns about the speed of vaccine development and testing; concerns about novel vaccine technologies; and rampant misinformation.

What can be done to build confidence and demand?

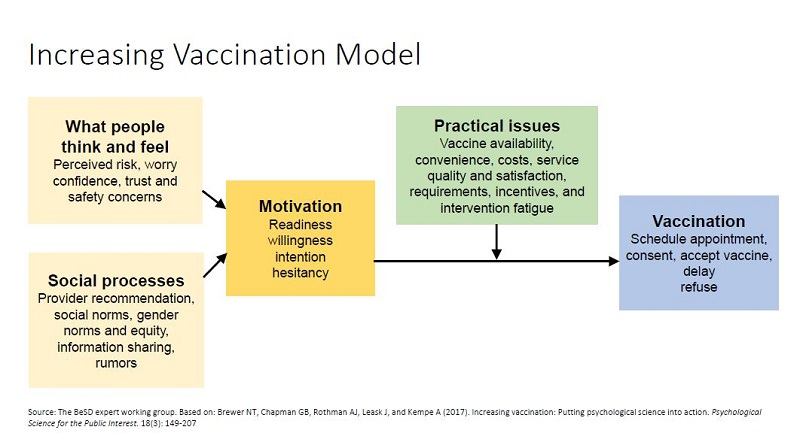

There are many factors that affect vaccination decisions,17 and individuals seek and are influenced by many sources.18 As indicated in the Increasing Vaccination Model19 (Figure 2), it is important to target and address attitudes, social processes, motivation, and access and other structural issues to nudge individuals toward vaccine acceptance.

There are several evidence-based approaches to build confidence and demand:

Avoid correcting misperceptions: The instinctive response to vaccine-related misinformation is to provide correct information. However, this approach can backfire20 – leading to something called the boomerang effect, which refers to a situation where a message generates the opposite attitude or behavior of what was intended.21 Attempts to correct false claims about vaccines may be especially likely to be counterproductive.

Pivot to focus on the disease: Instead of providing correct information when presented with vaccine-related misinformation, focus on the disease itself.20 To effectively stimulate action, health care providers and public health practitioners must be able to communicate in a way that an individual perceives themselves at risk for disease (risk perception), believes there is an effective action (response efficacy), and has confidence (self-efficacy) that they are capable of taking that action.22

Use presumptive communication: The use of a presumptive format within a vaccine conversation is a promising approach in structuring the vaccine encounter.23 This format linguistically presupposes that individuals will vaccinate, and therefore frames vaccination as the default, or normative behavior.19

Utilize motivational interviewing: Motivational interviewing is one communication strategy that has shown effectiveness in countering vaccine hesitancy and has been rigorously evaluated in clinical trials. Motivational interviewing focuses on leveraging an individual’s intrinsic motivation for engaging or not engaging in certain health behaviors and uses tools such as active listening, reflections, open-ended questions, asking permission to provide additional information, and acknowledging autonomy as a means to strengthen the perception that the clinician and patient are working together toward a common goal.24

Build trust through empathy: It is important to listen to individuals who are uncertain about a vaccine decision. Although vaccines are recommended from a public health perspective, individuals who hold concerns must feel as though their concerns are being heard and that health care providers and public health practitioners are empathetic to concerns.25 This is key to building trust and nudging those that may be vaccine hesitant toward vaccine acceptance.26

Tailor communication efforts: A nuanced form of communication that has shown some promise in mitigating hesitancy is tailoring. Tailoring includes matching each individual’s specific beliefs, attitudes, and experiences to the messages or information they are provided, thus improving the personal relevance of the information, and the likelihood that it will change behavior.27

Communicate often and transparently: In addition to building trust through empathy, communication is also critical to building trust. Communication about a vaccine – including the vaccine development process, allocation and distribution, and safety and efficacy issues – should be frequent and transparent.28 Proactive communication, even with incomplete information, is crucial.29

We are currently living in an infodemic – there is an excessive amount of information available related to vaccines, and many consumers are struggling with identifying what is accurate to best meet the needs of their families’ health.30 Health care providers and public health practitioners must continue to develop clear, evidence-based, and practically implementable approaches to mitigate vaccine hesitancy and build trust in immunization.

References

- Rappuoli R, Pizza M, Del Giudice G, De Gregorio E. Vaccines, new opportunities for a new society. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(34):12288-12293. doi:10.1073/pnas.1402981111

- Phadke VK, Bednarczyk RA, Salmon DA, Omer SB. Association Between Vaccine Refusal and Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in the United States. JAMA. 2016;315(11):1149-1158. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.1353

- Kennedy J. Vaccine Hesitancy: A Growing Concern. Paediatr Drugs. 2020;22(2):105-111. doi:10.1007/s40272-020-00385-4

- Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger J. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1763-1773. doi:10.4161/hv.24657

- Salmon DA, Dudley MZ, Glanz JM, Omer SB. Vaccine Hesitancy: Causes, Consequences, and a Call to Action. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(6 Suppl 4):S391-398. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.009

- Chater N. Facing up to the uncertainties of COVID-19. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4(5):439. doi:10.1038/s41562-020-0865-2

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nature Medicine. 2021;27(2):225-228. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9

- Barbacariu CL. Parents’ Refusal to Vaccinate their Children: An Increasing Social Phenomenon Which Threatens Public Health. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2014;149:84-91. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.08.165

- Wheelock A, Thomson A, Sevdalis N. Social and psychological factors underlying adult vaccination behavior: lessons from seasonal influenza vaccination in the US and the UK. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2013;12(8):893-901. doi:10.1586/14760584.2013.814841

- Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007-2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150-2159. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081

- Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):775-779. doi:10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y

- Callaghan T, Moghtaderi A, Lueck JA, et al. Correlates and Disparities of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Social Science Research Network; 2020. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3667971

- Limaye RJ, Sauer M, Ali J, et al. Building trust while influencing online COVID-19 content in the social media world. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2(6):e277-e278. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30084-4

- Quinn SC, Lama Y, Jamison A, Freimuth V, Shah V. Willingness of Black and White Adults to Accept Vaccines in Development: An Exploratory Study Using National Survey Data. Am J Health Promot. Published online December 28, 2020:890117120979918-890117120979918. doi:10.1177/0890117120979918

- Karpman M, Zuckerman S, Gonzalez D, Kenney GM. Confronting COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Nonelderly Adults. Urban Institute; 2021:21.

- Wouters OJ, Shadlen KC, Salcher-Konrad M, et al. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. The Lancet. 2021;397(10278):1023-1034. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00306-8

- Opel DJ, Heritage J, Taylor JA, et al. The Architecture of Provider-Parent Vaccine Discussions at Health Supervision Visits. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1037-1046. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2037

- Recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee: Standards for Adult Immunization Practice. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(2):115-123.

- Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Rothman AJ, Leask J, Kempe A. Increasing Vaccination: Putting Psychological Science Into Action. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2017;18(3):149-207. doi:10.1177/1529100618760521

- Omer SB, Amin AB, Limaye RJ. Communicating About Vaccines in a Fact-Resistant World. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(10):929-930. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2219

- Hart PS, Nisbet EC. Boomerang Effects in Science Communication: How Motivated Reasoning and Identity Cues Amplify Opinion Polarization About Climate Mitigation Policies - P. Sol Hart, Erik C. Nisbet, 2012. Communication Research. 2012;39(6):701-723.

- Witte K. Fear control and danger control: A test of the extended parallel process model (EPPM). Communication Monographs. 1994;61(2):113-134. doi:10.1080/03637759409376328

- Diekema DS, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics. Responding to parental refusals of immunization of children. Pediatrics. 2005;115(5):1428-1431. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0316

- Miller WR. Motivational interviewing: research, practice, and puzzles. Addict Behav. 1996;21(6):835-842. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(96)00044-5

- Limaye RJ, Malik F, Frew PM, et al. Patient Decision Making Related to Maternal and Childhood Vaccines: Exploring the Role of Trust in Providers Through a Relational Theory of Power Approach. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47(3):449-456. doi:10.1177/1090198120915432

- Greenberg J, Dubé E, Driedger M. Vaccine Hesitancy: In Search of the Risk Communication Comfort Zone. PLoS Curr. Published online March 3, 2017. doi:10.1371/currents.outbreaks.0561a011117a1d1f9596e24949e8690b

- Lustria MLA, Noar SM, Cortese J, Van Stee SK, Glueckauf RL, Lee J. A meta-analysis of web-delivered tailored health behavior change interventions. J Health Commun. 2013;18(9):1039-1069. doi:10.1080/10810730.2013.768727

- Sauer MA, Truelove S, Gerste AK, Limaye RJ. A Failure to Communicate? How Public Messaging Has Strained the COVID-19 Response in the United States. Health Security. 2021;19(1):65-74. doi:10.1089/hs.2020.0190

- Bahri P, Castillon Melero M. Listen to the public and fulfil their information interests - translating vaccine communication research findings into guidance for regulators. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(8):1696-1705. doi:10.1111/bcp.13587

- Zarocostas J. How to fight an infodemic. The Lancet. 2020;395(10225):676. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X