JHU has stopped collecting data as of

After three years of around-the-clock tracking of COVID-19 data from...

Vaccination, Transmission, and Masks

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of either Johns Hopkins University and Medicine or the University of Washington.

- We do not yet know whether individuals who are fully vaccinated can transmit SARS-CoV-2 to other individuals, although the risk is almost certainly lower than for unvaccinated persons

- To limit transmission as much as possible, mask wearing remains critical, even for those who are fully vaccinated until community transmission decreases to low levels and a high proportion of people are vaccinated

- Studies to better understand the potential for transmission by those who are fully vaccinated are underway, but they will take time to complete

Probably the biggest public health policy issue facing us today – and an issue each one of us will have to consider as the U.S. mass vaccination campaign continues to roll out – is what to do about wearing a mask once you’re fully vaccinated while many around you are not? No one likes masks, including me. But I understand how many gazillion viral particles can be put on the head of a pin and how many gazillion viral particles can be emitted through a sneeze, or while talking, or eating. And I understand how evolution has made this the mode of transmission for hundreds and hundreds of viruses – far too numerous to list here; these little critters were here on the planet well before us and pass from human to human without recrimination.

The good news for us in the fight against COVID-19 is that we now have three very effective vaccines – two mRNA (Pfizer and Moderna), and one Ad26 (Johnson & Johnson) – approved in the U.S. under Emergency Use Authorization that provide personal protection against symptomatic COVID-19, and millions of Americans have now been fully immunized. But what about those unvaccinated persons around you? Are they protected? Can you still acquire the virus unknowingly and transmit it? The CDC put out new guidance on social distancing for fully immunized people on Monday, March 8th. We need to think about this new guidance and what we know and don’t know about SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

First, let’s look at what happens when you come into contact with the virus and how protection works in your body.

When the virus lands on your hands and you touch your eyes or your nose or your mouth, it really becomes a race between your immune response and the virus’s ability to invade cells and start replicating. That race differs, depending on the virus, the inoculation load, the strain of the virus, and your own immune response. How good are the first immune system “soldiers,” often not primed by vaccination; how quick are the second line of soldiers – do they get into the nose, and how many get into the nose? There’s a fair amount of work that’s been done on what we call the battlefield between the host and the virus. And for many fast-replicating viruses, the half-life of a viral-infected cell is 20 to 40 minutes. So, every twenty-minute delay in an immune response can lead to a doubling, sometimes a tripling of the virus. This interplay tends to happen in what I’ll call staccato time; it certainly is not adagio.

But once you’re vaccinated, you are protected from getting severely ill or dying. What we don’t yet know is: can the virus still infect you and replicate at high enough levels that you could unwittingly transmit it to someone else? That’s the question we’re asking today. If the person is vaccinated, this may not be a big deal. But if they’re not vaccinated and they have an underlying medical condition, then we could have a problem. A problem that leads to hospitalization or worse, death.

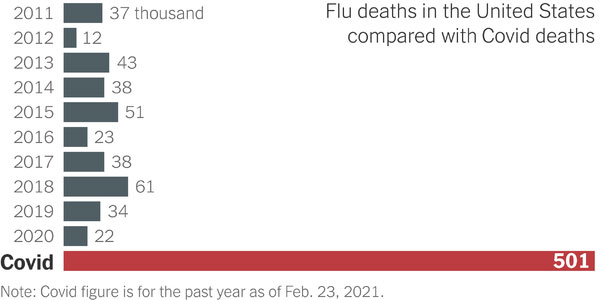

The potential severity of COVID-19 continues to stagger the imagination. Data collected over the past year grimly prove that early assertions calling COVID-19 simply the flu were false. A graph recently shown in the New York Times illustrates my point:

It’s this knowledge that I carry with me from day to day as a reminder: “Larry, you’re vaccinated, but a lot of people aren’t. In fact, 90% of the people walking around are not vaccinated and you do not have the luxury to give up your responsibility to protect them.”

So, this issue of mask wearing? Once you’re vaccinated, it’s really not about you at all. It’s about the other person. Maybe a friend or family member or neighbor or colleague that attends the same event or gathering but has not had the opportunity to be vaccinated. Or even someone who has chosen not to be vaccinated: do they deserve to get ill?

One might ask, a year into this pandemic, why don’t we know whether being vaccinated will prevent transmission? We don’t know this because the kinds of studies required to look at transmission are different from the ones designed to test vaccine efficacy. The clinical trials testing vaccine efficacy showed personal benefit – in other words, if you get vaccinated, will you be protected? And the answer to that as we’ve seen is yes, for all three of the vaccines currently authorized for use and being distributed in the U.S. But looking at transmission is a different matter altogether.

In the phase 3 trials there were thousands and thousands (approximately 30,000 participants) who were tested regularly (approximately once a week) to see if they got symptomatic COVID-19. But to test whether the virus was colonizing in the nose would have required near-daily testing. And if you pause to consider that – 30,000 persons over five months – with each person coming in daily to get their nose swabbed, it would have become impossible to test all the cultures in a timely way. We would have been diverted from defining vaccine efficacy.

It is possible to take fewer people and do what we call a transmission study, which is currently being conducted with the mRNA vaccines. We will look at vaccinated versus unvaccinated persons and determine if vaccination prevents you from transmitting the virus. This will require intensive contact tracing – looking at the contacts, who got infected, who didn’t? Who came first; who came second? Can we define exactly this person got it from that person? Sometimes the genetics of the virus allows one to do that.

The emerging variants also complicate things because they have been shown to be more infectious. For example, the B.1.1.7 strain first seen in the UK has been shown to cause 30% more infections. It appears to be shed for a substantially longer period of time than the G614D strain, which makes it more infectious. As the virus adapts, these new strains will cause a stress on vaccinations. But I think we can almost be happy that we’re doing the transmission study during the period of time when the virus is changing because we really do get at the relevant issue of how well these vaccines perform when the virus is starting to mutate.

So, we are getting to answers, but it will take some time. With a little luck, the transmission study will show the mRNA vaccines are spectacular at working to prevent COVID-19 altogether. Or if you do acquire it, the viral loads are trivial, and you won’t transmit it to anyone else. I’m hoping that’s the result because I want to take off my mask. But until we know this with reasonable certainty, or at least until more of our population is vaccinated, then public policy – and individual conscience – should mandate mask use in public spaces and any but small gatherings in our homes. The CDC guidance is clear that fully immunized people can meet each other at home, in small groups, without mask wearing and social distancing, but we’re going to have to maintain vigilance in public spaces, at work, on public transport, and at schools as they reopen. Mathematical modeling shows that without adhering to these measures, we could double the deaths. How each one of us behaves makes a difference. Together, we can markedly influence the surges associated with this virus and potentially save lives.